For public health dentists, it’s about helping those who need it most

'We're one of the smallest dental specialties but make the greatest impact'

Editor's note: This is the first article in a series that celebrates the diversity of career paths in dentistry and the Association's efforts in supporting dentists' career choices in the profession.

Huong Le, D.D.S., was in the process of buying a pediatric practice when she reached a fork in the road in her career path.

With her husband serving as a physician in the U.S. Air Force, the possibility of being reassigned caused her to second guess becoming a practice owner.

At around the same time, Dr. Le had decided to help a community clinic in Olivehurst, California, by working there one day a week.

"Thatwas about 33 years ago," Dr. Le said. "Once I started at the community clinic, I felt that commitment to the community, and the rest is history."

Suddenly, she found herself leaving her hospital job to become a staff dentist, and later the dental director, at the community clinic, where she stayed for 14 years. And in the last 19 years, Dr. Le has served as chief dental officer of Asian Health Services in Oakland, California, overseeing six dental sites that serve low-income and uninsured Bay Area residents.

Dr. Le is among the 3% of the dental workforce, or about 6,000 dentists, who primarily practice in dental safety net settings, which include health centers, community clinics, health departments, government programs and federal dental services. Others who primarily address the public health from the community perspective are educators at dental and public health schools, researchers, administrators, advocates and policymakers. About 800 of these dentists have advanced training in public health dentistry. In addition, there are about 215 dentists who are board certified in dental public health, according to the American Board of Public Health. A common theme for all public health dentists is a commitment to address the oral health of a community.

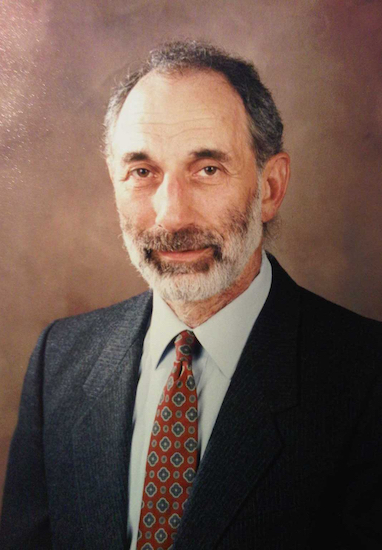

"We're one of the smallest dental specialties but make the greatest impact," said Myron Allukian Jr., D.D.S., whose career included stints as being the city of Boston's dental director, becoming a leading advocate of community water fluoridation, initiating programs for the underserved, homeless and persons with HIV/AIDS, and serving as president of the American Public Health Association, American Association of Community Dental Programs, American Association of Public Health Dentistry and the American Board of Dental Public Health. He also teaches at the three dental schools in Boston, Harvard, Tufts and Boston University.

Dr. Allukian, who today is often called "The Social Conscience of Dentistry," illustrates the importance of public health dentists with a simple allegory.

"Imagine a wide river flowing through a city, and the only way to cross it is to swim," he said. "As people cross, many drown."

This imaginary city, he continued, hires more and more lifeguards. But soon that becomes too expensive and unsustainable.

"It's the public health professionals who study why people are drowning (epidemiology) and find ways to solve the problem (policies/programs)," he said. "They'll determine the best places to build bridges. They'll determine who needs swimming lessons. That's what we do as public health dentists. We collect data, assess the oral health needs and resources of communities, and address those needs with policies and programs, then evaluate them to make sure they work."

'Path to healthier lives'

The ADA recognizes the role of public health in improving the oral health in the U.S., and the importance of dentists who pursue this career path.

"Every day, dentists in public health settings contribute to the well-being of individual patients and, over time, they set entire communities on the path to healthier lives," said ADA President Cesar R. Sabates, D.D.S. "Their provision of essential dental care to underserved populations is key in improving equity in our nation, which has long been a priority at the ADA."

Dr. Sabates launched his "A New Day for Dentistry" campaign, which is a celebration of the Association's diverse community of dentists. The campaign celebrates dentists' personal differences and the different career paths they've chosen within the profession.

The Association partners with several organizations and agencies including the National Network for Oral Health Access, the American Institute for Dental Public Health, the U.S. Public Health Service and the Indian Health Service to help dentists involved in public health succeed.

In 2014, the ADA launched Action for Dental Health, a community-based movement that seeks to address the oral health crisis in America by focusing on three main objectives: providing care now for people suffering from untreated disease; strengthening and expanding the public and private safety net; and preventing dental disease through advocacy education.

These objectives are supported by several solutions, including those involving public health approaches:

- Fluoridation: By working with local and state dental societies, Action for Dental Health seeks to ensure that at least 77% of the population served by public water systems has access to fluoridated water by 2030.

- Medicaid reform: The ADA advocates for increased dental health protections under Medicaid, especially in states that have yet to agree to Medicaid expansion, and helps more dentists work with community health centers and clinics to provide care for those in need.

- Community dental health coordinators (CDHCs): Similar to community health workers, these professionals address barriers to effective oral health care by helping underserved patients navigate the public health resources available in their communities, as well as connect to dentists for needed treatment.

- FQHCs: These safety-net facilities provide oral health care for underserved populations.

"Our collaboration with and support of dentists in public health settings is a major component of the ADA's efforts to drive public health forward," Dr. Sabates said.

Challenges and benefits

For Alayna Schoblaske, D.M.D., a dentist in a federally qualified health center in Medford, Oregon, there's been a lot to love with spending her first three years as a dentist working at an FQHC.

"I love our mission. I love that I get to work with nine other dentists and learn from them," she said. "And I love that I've been able to pursue leadership opportunities within the clinic."

For one year before dental school, Dr. Schoblaske worked on the administrative staff for the nonprofit Teach For America.

"I saw how dentistry can impact a child's school experience," she said. "I think that's what really solidified my decision to focus on public health dentistry."

At Oregon Health & Science University School of Dentistry, she collaborated with other students to start a free clinic and volunteered with the Health Equity Circle, an organization that seeks to address inequities in health care. She graduated in 2017 and completed a one-year general practice residency.

Her dental school experiences, she said, helped prepare her for some of the challenges she faces in her public health career.

"A significant challenge is navigating financial decisions with patients," Dr. Schoblaske said. Although the clinic offers a sliding fee scale for its services, cost barriers can still impact treatment decisions, such as choosing to extract a tooth instead of saving it with a more expensive root canal and crown.

At La Clinica, Dr. Schoblaske serves a unique demographic of patients; about 54% of her patients have Medicaid, and about 10% of her patients are experiencing homelessness.

"I'm not a social worker, but as a public health dentist, I do find myself hearing a lot about the unique challenges and barriers that my patients face in our society," Dr. Schoblaske said. "It does take extra effort."

With any large organization such as Dr. Schoblaske's clinic, there are also challenges when adapting to systems that she may not agree with or understand.

Dr. Le said working in a community health center often requires a specific frame of mind.

"Community health centers are all different. They each have their own policy and protocols," she said. "Unlike private dentists, there are times when you can't just call your own shots. And that can be hard for some people."

However, many of the upsides outweigh the challenges. Along with the fulfillment that comes from helping underserved people attain better oral health, careers in public health dentistry offer benefits ranging from leadership opportunities to assistance in paying off student debt.

Dr. Schoblaske left dental school with about $280,000 in student debt. With an extended four-year commitment with the National Health Service Corps loan repayment program, she will receive $140,000 in tax-free loan repayment.

Dr. Le added that being in public health also guarantees dentists a consistent salary, health insurance, ample sick leave, vacation days and other benefits.

"And although the starting salary may be lower than your fellow dentists, there's opportunity for growth in the long-run," Dr. Le said.

Of course, Dr. Schoblaske said, the most rewarding benefit is knowing her work is increasing access to care for the underserved.

"How cool is it that we get to help patients who may not have found help anywhere else?" Dr. Schoblaske said.

Considering public health

Dr. Allukian had little understanding of public health while at the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine in the 1960s. He had planned on going into private practice.

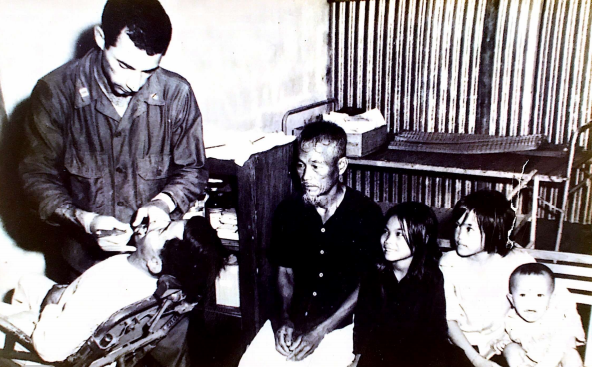

But while serving in the Navy during the Vietnam War and working at the 3rd Marine Division field hospital mass casualty unit, in his free time he initiated programs to provide dental care to children in nearby orphanages, schools, villages and refugee camps.

"As a thank you, the kids at the Buddhist orphanage would sing a song," he said. "When I heard that song, I said to myself that this is the kind of dentist I want to be."

When he returned to the U.S., he enrolled in Harvard's three-year dental public health program to pursue a career in international dentistry. But in 1968, while preparing to testify before the state legislature on a new fluoridation law, he found that Massachusetts 16-year-olds had six times more tooth decay than their Vietnamese counterparts.

"That finding led me to address the oral health care needs closer to home," said Dr. Allukian, who was raised in Boston. Soon, his focus turned to prevention, including taking an active role in promoting the dental health benefits of fluoridation. His efforts helped influence a new state fluoridation law that increased the percent of the population on a public water supply with fluoridation from 7% to 63%, reaching 4 million people.

"The ADA has been a great resource on this issue in expanding access to fluoridation, which is the foundation for better oral health for everyone," Dr. Allukian said. The Association fully endorses and advocates for the fluoridation of community water supplies as safe, effective and necessary in preventing tooth decay.

One of the things he tells dental students on why they should consider a career in public health is the potential to help a wider population - whether it's a few thousand residents in a small rural community or millions in a metropolitan city or state.

Like Dr. Allukian, Dr. Le has taken on more leadership opportunities - larger roles than she first imagined when she took on a one-day-a-week job in a small rural community clinic 33 years ago. She became the first Vietnamese American on the Dental Board of California and has served as president of the National Network for Oral Health Access.

When students and residents from Bay Area dental schools do their rotations at her clinics, Dr. Le doesn't hesitate to encourage them to take or support the public health career path.

"There's nothing wrong with private practice or pursuing other careers in dentistry," Dr. Le said. "But I tell them that whatever they choose, that they don't forget about the larger community and offer any help they can."